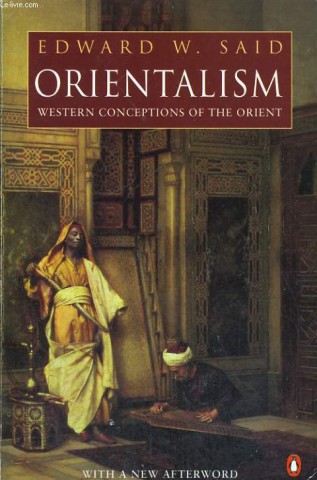

Orientalism

Few books have been as widely read and cited as Orientalism (1978) by Edward Said. Reading Orientalism now, it is hard to understand its importance because so many of Said's ideas have become part of a broader cultural and post-colonial critiques. Despite its influence, in a 2003 Preface, the author writes: "The disheartening part is that the more the critical study of cultural shows us that this is the case, the less influence such a view seems to have, and the more territorially reductive polarizations like "Islam v. the West" seem to conquer" (p. xxiii). More people understand the message, but it appears to carry less weight. One may disagree with the book, or specific points made within it, but it should be on everyone's essential reading list.

Said writes of a deep history wherein the study of others – specifically Arabs and Muslims – has entrenched ideas of superiority, and for centuries portrayed Arabs and Muslims as lesser than human, irrational, evil. "These contemporary Orientalist attitudes flood the press and the popular mind. Arabs, for example, are thought of as camel-riding, terroristic, hook-nosed, venal lechers whose underserved wealth is an affront to real civilization. Always there lurks the assumption that although the Western consumer belongs to a numerical minority, he is entitled either to own or to expend (or both) the majority of the world resources. Why? Because he, unlike the Oriental, is a true human being" (p. 108). Importantly, these portrayals are means of self-definition – what "they" are, and what "we" are not; what "we" are, and what "they" are not. Said begins his book in stating that the "Orient has helped to define Europe (or the West) as its contrasting image, idea, personality, experience (p. 1-2).

At its core, this is a book not about portrayal of others, it is a book about what that portrayal means when the individual, group, nation or Empire conveying it has power and authority. "There is nothing mysterious or natural about authority. It is formed, irradiated, disseminated; it is instrumental, it is persuasive; it has status, it established canons of tastes and value; it is virtually indistinguishable from certain ideas it dignifies as true, and from traditions, perceptions, and judgements it forms, transmits, reproduces. Above all, authority can, indeed must, by analyzed" (p. 19-20). That power and authority, in the realm of ideas, can be reinforcing: "If one reads a book claiming that lions are fierce and then encounters a fierce lion (I simplify, of course), the changes are that one will be encourages to read more books by that same author, and believe them" (p. 93)

In the portrayal of others, Said argues, there is something more than incorrect information. These portrayals of others as lesser than human serves a purpose, it is a tactic and a tool that is intentionally utilized: "My whole point about this system is not that it is a misinterpretation of some Oriental essence – in which I do not for a moment believe – but that it operates as representations usually do, for a purpose, according to a tendency, in a specific historical, intellectual, and even economic setting. In other words, representations have purposes, they are effective much of the time, they accomplish one or many tasks" (p. 273). Consider the author's assessment of Arabs and Muslims in the media – and recall that this is Said writing in 1978, not 2016:

"the Arab is associated either with lechery or bloodthirsty dishonesty. He appears as an oversexed degenerate, capable, it is true, of cleverly devious intrigues, but essentially sadistic, treacherous, low. Slave trader, camel driver, moneychanger, colorful scoundrel: these are some traditional Arab roles in the cinema. The Arab leader (of marauders, pirates, "native" insurgents) can often be seen snarling at the captured Western hero and the blond girl (both of them steeped in wholesomeness), "My men are going to kill you, but – they like to amuse themselves before." He leers suggestively as he speaks: this is a current debasement of Valentino's Sheik. In newsreels or newsphotos, the Arab is always shown in large numbers. No individuality, no personal characteristics or experiences. Most of the pictures represent mass rage and misery, or irrational (hence hopelessly eccentric) gestures. Lurking behind all of these images is the menace of jihad. Consequence: a fear that the Muslims (or Arabs) will take over the world. Books and articles are regularly published on Islam and the Arabs that represent absolutely no change over the virulent anti-Islamic polemics of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance" (p. 286-287).

In the 2003 Preface Said speaks of a responsibility – not of one's choosing but of "force of circumstance" – of those who cross boundaries and can transmit and translate ideas between worlds: "For those of us who by force of circumstance actually live the pluri-cultural life as it entails Islam and the West, I have long felt that a special intellectual and moral responsibility attaches to what we do as scholars and intellectuals. Certainly, I think it is incumbent upon us to complicate and/or dismantle the reductive formulae and the abstract but potent kind of thought that leads the mind away from concrete human history and experience and into the realms of ideological fiction, metaphysical confrontation, and collective passion" (p. xxiii).