Thinking about people and objects as components in interconnected, non-linear and dynamic systems, rather than as compartmentalized and independent actors, began to take shape during the early 1900s with work by the biologist Von Bertalanffy. Throughout the last century, the systems approach was applied in a wide range of areas of inquiry, and has been used as an approach to understand how systems work, and therefore engage with the system in a way that recognizes its interrelated components. As it relates to understanding and explaining change, systems-based thinking is concerned with how dynamic interactions and interconnected relationships affect one another in systematic ways. In other words, individuals are embedded within complex adaptive systems.

One of the ways to understand change that builds upon systems theories is a complexity-based perspective founded in the idea that all change occurs within complex adaptive systems. Complexity theorists suggest that change takes place within complex and dynamic contexts and that actors cannot be understood in isolation. As such, understanding change requires analyses of the entire system, its interactions, relationships and feedback mechanisms. Ramalingam suggests that thinking about change as occurring within complex adaptive systems can foster more flexibility, creativity and innovation. However, it also poses practical challenges as a theory in practice. For example, it is not clear how much needs to be known in order to sufficiently understand the dynamics of non-linear systems, which are themselves embedded within layers of uncertainties.

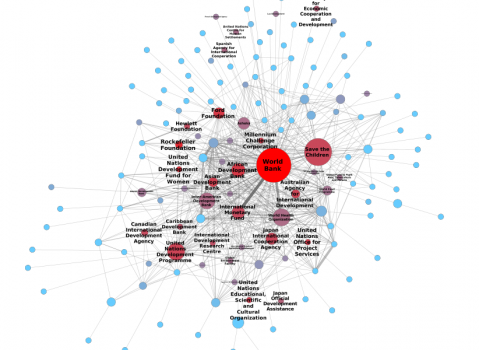

(Image from aidontheedge.info)

In his advocacy of thinking about change as operating within complex adaptive systems, Ramalingam presents an example familiar to ecological anthropologists: Balinese agricultural terracing systems. As identified by Lansing et al, resource management in this traditional agricultural system was practically optimal. External pressure that was exerted during the 1970s sought to modernize and improve the system, the result of which was a system failure. Rather than understanding the agricultural setting as a complex adaptive system, external parties suggested that specific changes would increase yields, while in the process significantly underestimating potential risks. Ramalingam suggests that it was Lansing's work in understanding the Balinese setting as a complex adaptive system that enabled "teasing out what had made the old system work so well for so long." As such, viewing change within agricultural systems as one component of a complex adaptive system, as Ramalingam advocates, enables change to be viewed as part of a larger system in order to put 'best-fit' before 'best-practice'.

The challenge with complexity in international development is trying to pull all the important pieces together. We have the value of hindsight in seeing the complexity in the Balinese terracing system. How do we apply complexity theory to international aid for the present and future?

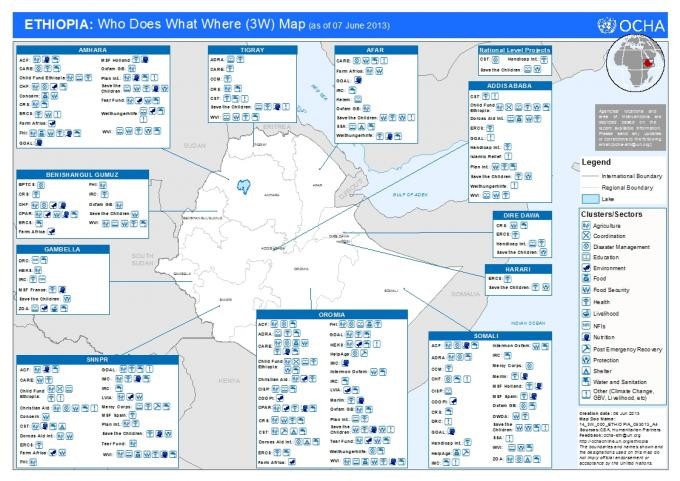

(Diversity of NGOs, activities and locations; Image from UN OCHA)

While life histories will not provide specific direction for international development planning or implementation, they may provide insight into the ways in which unrelated components interact over the long term, and help us answer think about better answers to those challenges. Consider:

Asha was born in a small town. Her father passed away, her mother struggled to keep the family afloat. She went to live with extended family. As a seven year old girl, Asha was abused by an uncle. In addition to the physical and psychosocial trauma, she acquired HIV. At the time, Asha did not know of her status and the country within which she lived did not provide treatment, had she known. At the time, stigma and discrimination were fueled by a lack of information and fear. After a serious illness Asha went to the doctor, which is when she learned of her status. Due to the fear and stigma, her extended family forced to leave. Asha'a brother arranged for her to enter a care facility, which he learned about via a government counseling and support service. Beginning in 2006, the government began to freely provide antiretroviral treatment for AIDS, with the support of a range of partners (including the World Health Organization, USAID and PEPFAR funding, the Global Fund and others). Before this time, most children living with HIV/AIDS lived short lives.

Asha entered a children's home, designed specifically to support children living with HIV/AIDS. The home was a partnership between a locally-based organization and a US-based charity. From the age of 11 until 17, Asha lived in this care home, which provided her basic needs. Asha's medical care was provided by another NGO, specializing in treating children living with HIV/AIDS. An independent psychologist provided her with counseling. Asha gained experience with a range of volunteers while growing up. She was supported in her passion to advocate for children living with HIV/AIDS, resulting in numerous speaking engagements, including at United Nations conference.

As someone excelling her in academic studies, Asha was offered a scholarship to attend a prestigious private school, where she completed high school. According to national law, children cannot live in home care facilities after the age of 18, so in preparation for that shift, Asha shifted to live with a couple working for an international organization, a connection developed via the network of individuals supporting the care home. This network supported Asha to apply for university scholarships, and she is currently completing a degree in a western country.

Asha'a story highlights how an individual organization, or project activity, can play an important role in the life on an individual and the direct impact can be quantified. However, the unrelated organizations and activities, as a collection of dynamic interactions and interconnected relationships, affect one another in systematic ways. It was not one intervention that impacted her life. It was individuals, community-based organizations, NGOs, universities, governments and international agencies, collectively, that enabled Asha to be the amazing success story that she is.

For systems and complexity theorists, the life story narrative enables us to analyze how a range of unknown actors, unanticipated changes, and unrelated activities connect within the life of an individual. It is unlikely that we will ever be able to know or predict all these factors and engage with them in a systematic, modelable fashion. Thus the challenge, and potentially the limit, of systems and complexity theories in international development; there are too many unknown, unpredictable and unrelated factors. That said, Asha's story also shows the value of systems and complexity theories in seeking to understand how change happens. In addition to the theoretical and programmatic value, mapping change backwards using life stories might enable us to think about organizations and activities in new ways. It may also enable us to engange in complex adaptive systems recognizing the limitations of complexity theories in explaining them, while using them to help understand how change happens, and keeping in mind that a particular NGO or project activity may not have all the required components to reach the desired result, but the complex adaptive system might.